Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

During the final stages of World War II in 1945, the Allies of World War II conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.

Following a firebombing campaign that destroyed many Japanese cities, the Allies prepared for a costly invasion of Japan. The war in Europe ended when Nazi Germany signed its instrument of surrender on 8 May, but the Pacific War continued. Together with the United Kingdom and the Republic of China, the United States called for a surrender of Japan in the Potsdam Declaration on 26 July 1945, threatening Japan with "prompt and utter destruction". The Japanese government ignored this ultimatum, and two nuclear weapons developed by the Manhattan Project were deployed. Little Boy was dropped on the city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, followed by the Fat Man over Nagasaki on 9 August.

Within the first two to four months of the bombings, the acute effects killed 90,000–166,000 people in Hiroshima and 60,000–80,000 in Nagasaki, with roughly half of the deaths in each city occurring on the first day. The Hiroshima prefecture health department estimated that, of the people who died on the day of the explosion, 60% died from flash or flame burns, 30% from falling debris and 10% from other causes. During the following months, large numbers died from the effect of burns, radiation sickness, and other injuries, compounded by illness. In a U.S. estimate of the total immediate and short term cause of death, 15–20% died from radiation sickness, 20–30% from burns, and 50–60% from other injuries, compounded by illness. In both cities, most of the dead were civilians, although Hiroshima had a sizeable garrison.

On 15 August, six days after the bombing of Nagasaki, Japan announced its surrender to the Allies, signing the Instrument of Surrender on 2 September, officially ending World War II. The bombings led, in part, to post-war Japan's adopting Three Non-Nuclear Principles, forbidding the nation from nuclear armament. The role of the bombings in Japan's surrender and their ethical justification are still debated.

Hiroshima:

At the time of its bombing, Hiroshima was a city of both industrial and military significance. A number of military camps were located nearby, including the headquarters of Field Marshal Shunroku Hata's 2nd General Army Headquarters, which commanded the defense of all of southern Japan. His command consisted of some 400,000 men, most of whom were on Kyushu where an Allied invasion was correctly expected. Also present in Hiroshima was the headquarters of the Fifty-Ninth Army, and most of the 224th Division, a recently formed mobile unit.The city's air defenses comprised five batteries of 7-centimetre (2.8 in) and 8-centimetre (3.1 in) anti-aircraft guns.

Hiroshima was a minor supply and logistics base for the Japanese military. The city was a communications center, a storage point, and an assembly area for troops. It was one of several Japanese cities left deliberately untouched by American bombing, allowing a pristine environment to measure the damage caused by the atomic bomb.

The center of the city contained several reinforced concrete buildings and lighter structures. Outside the center, the area was congested by a dense collection of small wooden workshops set among Japanese houses. A few larger industrial plants lay near the outskirts of the city. The houses were constructed of wood with tile roofs, and many of the industrial buildings were also built around wood frames. The city as a whole was highly susceptible to fire damage.

The population of Hiroshima had reached a peak of over 381,000 earlier in the war, but prior to the atomic bombing the population had steadily decreased because of a systematic evacuation ordered by the Japanese government. At the time of the attack, the population was approximately 340,000–350,000.

The bombing:

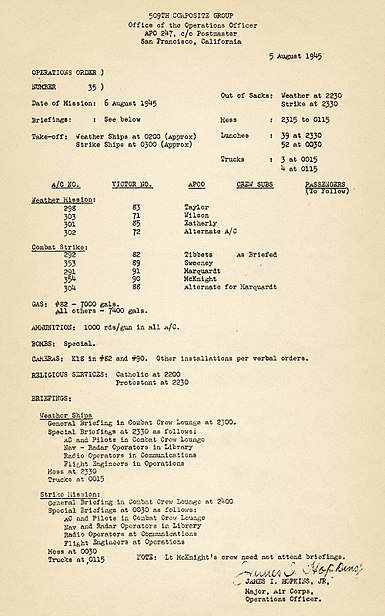

Hiroshima was the primary target of the first nuclear bombing mission on 6 August, with Kokura and Nagasaki as alternative targets. The 393d Bombardment Squadron B-29 Enola Gay, piloted by Tibbets, took off from North Field airbase on Tinian, about six hours flight time from Japan. The Enola Gay (named after Tibbets' mother) was accompanied by two other B-29s. The Great Artiste, commanded by Major Charles W. Sweeney, carried instrumentation, and a then-nameless aircraft later called Necessary Evil, commanded by Captain George Marquardt, served as the photography aircraft.

| Aircraft | Pilot | Call Sign | Mission role |

| Straight Flush | Major Claude R. Eatherly | Dimples 85 | Weather reconnaissance (Hiroshima) |

| Jabit III | Major John A. Wilson | Dimples 71 | Weather reconnaissance (Kokura) |

| Full House | Major Ralph R. Taylor | Dimples 83 | Weather reconnaissance (Nagasaki) |

| Enola Gay | Colonel Paul W. Tibbets | Dimples 82 | Weapon Delivery |

| The Great Artiste | Major Charles W. Sweeney | Dimples 89 | Blast measurement instrumentation |

| Necessary Evil | Captain. George W. Marquardt | Dimples 91 | Strike observation and photography |

| Top Secret | Captain Charles F. McKnight | Dimples 72 | Strike spare—did not complete mission |

After leaving Tinian the aircraft made their way separately to Iwo Jima where they rendezvoused at 2,440 meters (8,010 ft) and set course for Japan. The aircraft arrived over the target in clear visibility at 9,855 meters (32,333 ft). Parsons, who was in command of the mission, armed the bomb during the flight to minimize the risks during takeoff. His assistant, Second Lieutenant Morris Jeppson, removed the safety devices 30 minutes before reaching the target area.

About an hour before the bombing, Japanese early warning radar detected the approach of some American aircraft headed for the southern part of Japan. An alert was given and radio broadcasting stopped in many cities, among them Hiroshima. At nearly 08:00, the radar operator in Hiroshima determined that the number of planes coming in was very small—probably not more than three—and the air raid alert was lifted. To conserve fuel and aircraft, the Japanese had decided not to intercept small formations. The normal radio broadcast warning was given to the people that it might be advisable to go to air-raid shelters if B-29s were actually sighted. However a reconnaissance mission was assumed because at 07:31 the first B29 to fly over Hiroshima at 32,000 feet (9,800 m) had been the weather observation aircraft Straight Flush that sent a morse code message to the Enola Gay indicating that the weather was good over the primary target. Because it then turned out to sea, the 'all clear' was sounded in the city. At 08:09 Colonel Tibbets started his bomb run and handed control over to his bombardier.

The release at 08:15 (Hiroshima time) went as planned, and the gravity bomb known as "Little Boy", a gun-type fission weapon with 60 kilograms (130 lb) of uranium-235, took 43 seconds to fall from the aircraft flying at 31,060 feet (9,470 m) to the predetermined detonation height about 1,900 feet (580 m) above the city. The Enola Gay traveled 11.5 miles (18.5 km) before it felt the shock waves from the blast.

Due to crosswind, it missed the aiming point, the Aioi Bridge, by approximately 800 feet (240 m) and detonated directly over Shima Surgical Clinic. It created a blast equivalent to about 13 kilotons of TNT (54 TJ). (The U-235 weapon was considered very inefficient, with only 1.38% of its material fissioning.) The radius of total destruction was about one mile (1.6 km), with resulting fires across 4.4 square miles (11 km2).Americans estimated that 4.7 square miles (12 km2) of the city were destroyed. Japanese officials determined that 69% of Hiroshima's buildings were destroyed and another 6–7% damaged.

Some 70,000–80,000 people, or some 30% of the population of Hiroshima were killed immediately, and another 70,000 injured. Over 90% of the doctors and 93% of the nurses in Hiroshima were killed or injured—most had been in the downtown area which received the greatest damage.

|

| The Hiroshima Genbaku Dome after the bombing |

|

| The dark portions of the garments this victim wore during the flash caused burns on the skin |

|

| Small-scale recreation of the Nakajima area around ground zero |

|

| Strike order for the Hiroshima bombing as posted on 5 August 1945 |

Nagasaki:

I realize the tragic significance of the atomic bomb... It is an awful responsibility which has come to us... We thank God that it has come to us, instead of to our enemies; and we pray that He may guide us to use it in His ways and for His purposes.—President Harry S Truman, August 9, 1945

The city of Nagasaki had been one of the largest sea ports in southern Japan and was of great wartime importance because of its wide-ranging industrial activity, including the production of ordnance, ships, military equipment, and other war materials.

In contrast to many modern aspects of Hiroshima, almost all of the buildings were of old-fashioned Japanese construction, consisting of wood or wood-frame buildings with wood walls (with or without plaster) and tile roofs. Many of the smaller industries and business establishments were also situated in buildings of wood or other materials not designed to withstand explosions. Nagasaki had been permitted to grow for many years without conforming to any definite city zoning plan; residences were erected adjacent to factory buildings and to each other almost as closely as possible throughout the entire industrial valley.

Nagasaki had never been subjected to large-scale bombing prior to the explosion of a nuclear weapon there. On August 1, 1945, however, a number of conventional high-explosive bombs were dropped on the city. A few hit in the shipyards and dock areas in the southwest portion of the city, several hit the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works, and six bombs landed at the Nagasaki Medical School and Hospital, with three direct hits on buildings there. While the damage from these bombs was relatively small, it created considerable concern in Nagasaki and many people—principally school children—were evacuated to rural areas for safety, thus reducing the population in the city at the time of the nuclear attack. By early August the city was defended by four batteries of 7 centimetres (2.8 in) anti-aircraft guns and two searchlight batteries.

To the north of Nagasaki there was a camp holding British Commonwealth prisoners of war, some of whom were working in the coal mines and only found out about the bombing when they came to the surface. The bombing:

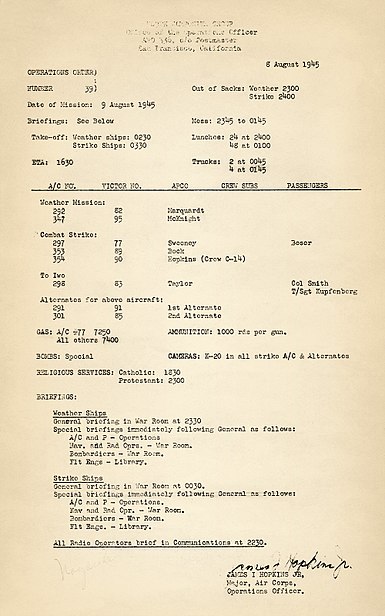

Responsibility for the timing of the second bombing was delegated to Tibbets. Scheduled for 11 August against Kokura, the raid was moved earlier by two days to avoid a five day period of bad weather forecast to begin on 10 August. Three bomb pre-assemblies had been transported to Tinian, labeled F-31, F-32, and F-33 on their exteriors. On 8 August, a dress rehearsal was conducted off Tinian by Sweeney using Bockscar as the drop airplane. Assembly F-33 was expended testing the components and F-31 was designated for the August 9 mission.

| Aircraft | Pilot | Call Sign | Mission role |

| Enola Gay | Captain George W. Marquardt | Dimples 82 | Weather reconnaissance (Kokura) |

| Laggin' Dragon | Captain Charles F. McKnight | Dimples 95 | Weather reconnaissance (Nagasaki) |

| Bockscar | Major Charles W. Sweeney | Dimples 77 | Weapon Delivery |

| The Great Artiste | Captain Frederick C. Bock | Dimples 89 | Blast measurement instrumentation |

| Big Stink | Major James I. Hopkins, Jr. | Dimples 90 | Strike observation and photography |

| Full House | Major Ralph R. Taylor | Dimples 83 | Strike spare—did not complete mission |

On the morning of 9 August 1945, the B-29 Superfortress Bockscar, flown by Sweeney's crew, carried Fat Man, with Kokura as the primary target and Nagasaki the secondary target. The mission plan for the second attack was nearly identical to that of the Hiroshima mission, with two B-29s flying an hour ahead as weather scouts and two additional B-29s in Sweeney's flight for instrumentation and photographic support of the mission. Sweeney took off with his weapon already armed but with the electrical safety plugs still engaged.

This time Penney and Cheshire were allowed to accompany the mission, flying as observers on the third plane, Big Stink, which flown by the group's Operations Officer, Lieutenant Colonel James I. Hopkins, Jr. Observers aboard the weather planes reported both targets clear. When Sweeney's aircraft arrived at the assembly point for his flight off the coast of Japan, Big Stink, failed to make the rendezvous. Bockscar and the instrumentation plane circled for 40 minutes without locating Hopkins. Already 30 minutes behind schedule, Sweeney decided to fly on without Hopkins.

By the time they reached Kokura a half hour later, a 70% cloud cover had obscured the city, prohibiting the visual attack required by orders. After three runs over the city, and with fuel running low because a transfer pump on a reserve tank had failed before take-off, they headed for their secondary target, Nagasaki. Fuel consumption calculations made en route indicated that Bockscar had insufficient fuel to reach Iwo Jima and would be forced to divert to Okinawa. After initially deciding that if Nagasaki were obscured on their arrival the crew would carry the bomb to Okinawa and dispose of it in the ocean if necessary, the weaponeer, Navy Commander Frederick Ashworth, decided that a radar approach would be used if the target was obscured.

At about 07:50 Japanese time, an air raid alert was sounded in Nagasaki, but the "all clear" signal was given at 08:30. When only two B-29 Superfortresses were sighted at 10:53, the Japanese apparently assumed that the planes were only on reconnaissance and no further alarm was given.

A few minutes later at 11:00, The Great Artiste, the support B-29 flown by Captain Frederick C. Bock, dropped instruments attached to three parachutes. These instruments also contained an unsigned letter to Professor Ryokichi Sagane, a nuclear physicist at the University of Tokyo who studied with three of the scientists responsible for the atomic bomb at the University of California, Berkeley, urging him to tell the public about the danger involved with theseweapons of mass destruction. The messages were found by military authorities but not turned over to Sagane until a month later. In 1949, one of the authors of the letter, Luis Alvarez, met with Sagane and signed the document.

At 11:01, a last minute break in the clouds over Nagasaki allowed Bockscar's bombardier, Captain Kermit Beahan, to visually sight the target as ordered. The Fat Man weapon, containing a core of about 6.4 kilograms (14 lb) of plutonium, was dropped over the city's industrial valley. It exploded 43 seconds later at 469 metres (1,539 ft) above the ground halfway between the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works in the south and the Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works (Torpedo Works) in the north. This was nearly 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) northwest of the planned hypocenter; the blast was confined to the Urakami Valley and a major portion of the city was protected by the intervening hills. The resulting explosion had a blast yield equivalent to 21 kilotons of TNT (88 TJ). The explosion generated heat estimated at 3,900 °C (7,050 °F) and winds that were estimated at 1,005 km/h (624 mph).

Casualty estimates for immediate deaths range from 40,000 to 75,000. Total deaths by the end of 1945 may have reached 80,000. At least eight known POWs died from the bombing and as many as 13 POWs may have died, including a British Commonwealth citizen, and seven Dutch POWs. One American POW, Joe Kieyoomia, was in Nagasaki at the time of the bombing but survived, reportedly having been shielded from the effects of the bomb by the concrete walls of his cell. The radius of total destruction was about 1 mile (1.6 km), followed by fires across the northern portion of the city to 2 miles (3.2 km) south of the bomb. The Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works, the factory that manufactured the type 91 torpedoes released in the attack on Pearl Harbor, was destroyed in the blast. There is also a peace monument and Bell of Nagasaki in the Kokura.

|

| A photograph of Sumiteru Taniguchi's back injuries taken in January 1946 by a U.S. Marine photographer |

|

Strike order for the Nagasaki bombing as posted 8 August 1945 |

|

| A Japanese report on the bombing characterized Nagasaki as "like a graveyard with not a tombstone standing" |

|

| The black marker indicates "ground zero" of the Nagasaki atomic bomb explosion |

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment